Let’s start with the good news. K-3 Literacy Programs are dynamic – the content and goals of K-3 Literacy Programs shift in response to the needs of local stakeholders and the growing body of legislation drafted to promote accountability, equity, and access. Now comes the challenge (the opportunity!). How do you, a district decision-maker, evaluate the ever-evolving curricular options and products that develop to fill the niches formed by changing legislation and student needs?

In 2021, the state of Illinois, for example, enacted 69 bills related to education with policy areas including accountability, assessment, curriculum, standards, teaching, and more.

Education Commission of the States, 2021

Knowing that the curriculum you choose and use needs to meet state standards, how do you know what evidence to look for to satisfy requirements and what evidence to trust? It’s difficult to cut through the marketing “noise” and figure out what might work for your students. Familiarizing yourself with the words, requirements, and claims related to evidence-based educational programs is a powerful step in choosing the best-fit options for your district.

Evidence & Research Terminology

Research base: A product’s description of the academic research that informs the design of a program: what a program covers (the content) and how it is taught (the pedagogy). This academic research may be primarily theoretical or have published studies that include students in a laboratory or school setting. This research does not provide evidence about this product working, but instead about the theories or practices that demonstrate a rationale for why the product should work.

Evidence base: A product’s collection of scientific, academic, or social proof that occurs when using a program improves learning outcomes. These stories may be formal (efficacy studies) or informal (case studies) and be conducted by the company that owns the product or by third-party researchers (sponsored by foundations, federal grants, or the companies themselves). This is research about the product working, and how compelling that evidence depends on the rigor of the methodology and the sample size (having at least 350 students in each group is considered a large study).

ESSA Evidence Levels: This is how you evaluate the rigor of the methodology. ESSA recognizes four levels of strength to evaluate the rigor of a research study’s methodology. The top three levels require findings of a statistically significant effect on improving student outcomes or other relevant outcomes.

- Level 1, Strong evidence: At least one well-designed and well-implemented experimental (i.e., randomized) study.

- Level 2, Moderate evidence: At least one well-designed and well-implemented quasi-experimental (i.e., matched) study.

- Level 3, Promising evidence: At least one well-designed and well-implemented correlational study with statistical controls for selection bias.

- Level 4 is a program or practice that does not yet have evidence qualifying for the top 3 levels, and can be considered evidence-building and under evaluation.

Quick question – what is a correlational study?

A correlations is a statistical analysis that compares two sets of scores with the same students and helps us understand the strength of the relationship between the tests. For example, if students make a lot of progress in an online program that is effective, they will have higher reading score gains at the posttest than students who make less progress, a positive correlation.

Efficacy: This term connects the research base and the evidence base, efficacy studies (that make up the evidence base) help measure to what extent a program produced its intended effect (inferred from the research base). The external reviewers of research use the statistical measure of the effect size to quantify the impact of that desired result. Similar to the correlation, this number measures the strength of a relationship. Efficacy studies and the effect size measure help us answer: how different were the scores of students in the product group compared to the scores of students in the comparison group?

Wait a minute, teachers and students use the program in real life. These studies are not happening in a research lab. What should I keep in mind about that?

Review research to see what, if any, variables are included in the analysis that measures a product’s effectiveness. Two phrases to look out for are:

Fidelity of implementation: How “well” was the product implemented? Was it similar or quite different to the designers’ suggested methods to produce the desired effects? This aspect of research is one of the most subjective and difficult to measure in a standardized way. Usually, studies include a teacher survey, classroom observations, and perhaps interviews with an administrator. Typically this information is not in the study summary or abstract, so you’ll have to dig a little deeper for it.

Accounting for Individual Variability: Also described as “controlling for a variable,” this statistical method helps researchers take into account local contextual factors. For example, if one school is in a more expensive part of town and a second is in a less expensive part of town, median housing prices in that district could help statistically remove the effect of household income on the other variables that are being tested (using the product or not, mainly).

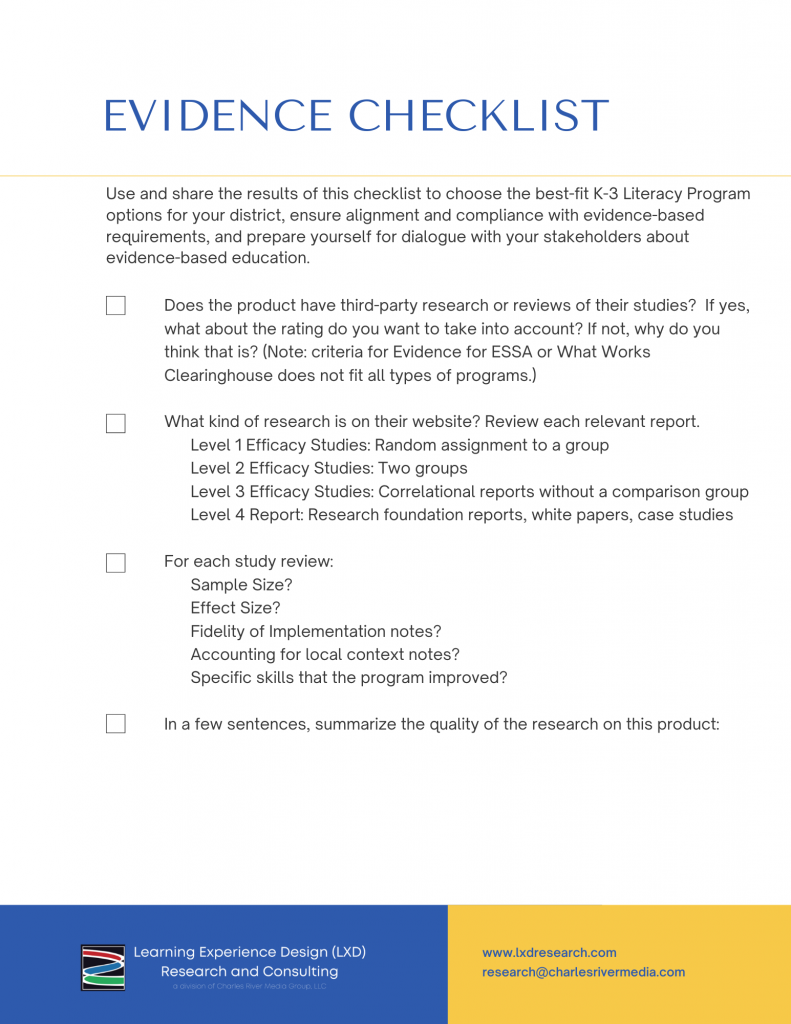

Knowing the large number of K-3 Literacy Programs you may consider in a curriculum review and adoption cycle, we have created an evidence-based screening checklist tool to support you in your efforts to carry out and model evidence-based decision-making in your community.

Download the checklist to help you conduct your research review.